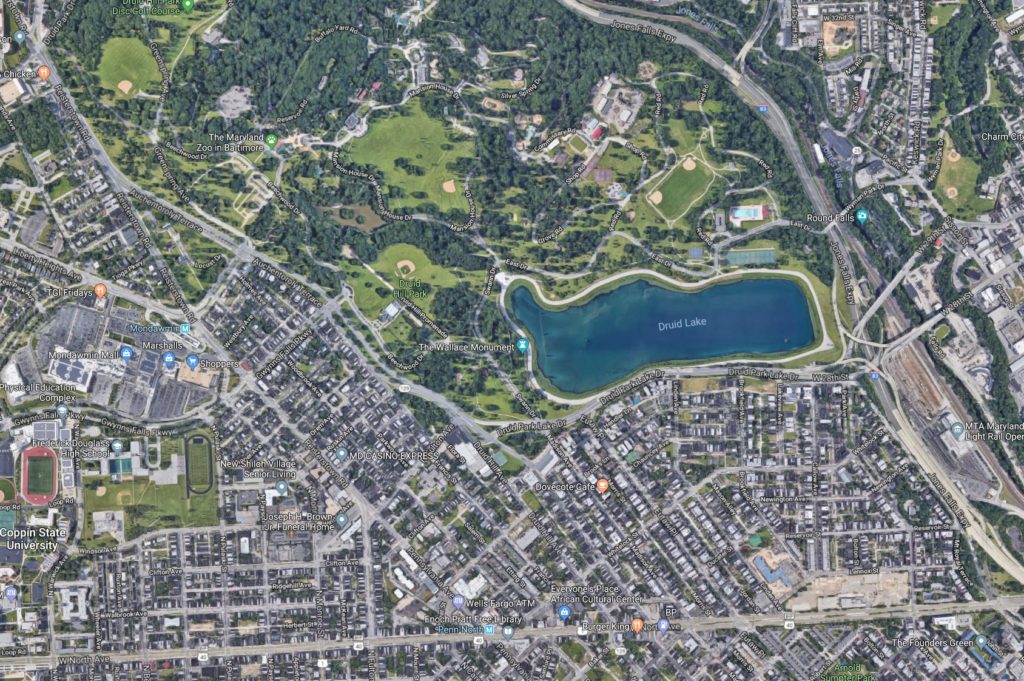

Public artist Graham Coreil-Allen spoke to us on a recent segment of Humanities Connection. Here, he uses photography to takes us through the history of Druid Hill Park’s infrastructure, its impact, and the efforts to make Druid Hill Park more accessible.

Recently a long row of orange and white plastic barriers appeared along Druid Park Lake Drive and across the 28th Street Bridge. This is the Big Jump Baltimore shared-use path. Championed by local residents, 7th District Councilman Leon Pinkett, Baltimore City Department of Transportation, and Bikemore, this temporary project counteracts decades of highway expansion with a protected space for pedestrians, wheelchair riders, and bicyclists. Neighbors and artists been creating public art along the Big Jump pathway to make it safer for all people to enjoy the cultural and health benefits of Druid Hill Park.

NAACP Labor Secretary Clarence Mitchell Jr. argued that increased traffic speeds through westside neighborhoods would imperil black residents effectively barred by racist real estate practices from moving to the very suburbs that the highway would serve. Shaarei Tifoloh synagogue Rabbi Nathan Drazin expressed concern that traffic would endanger children attending Hebrew school as well as the throngs of congregants who traditionally walked down the middle of Auchentoroly Terrace during the high holy days. Nevertheless, the local council members were asked by James Pollack, then head of the powerful Trenton Democratic Club, to ignore their constituent opposition and support what he considered to be a “citywide” highway effort. It didn’t hurt that plans for extending Auchentoroly Terrace just happened to end at Anoka Avenue – the calm, tree-lined street that Mr. Pollack called home.

In 1951 Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro Jr. proposed the Jones Falls Expressway. Druid Park Lake Drive would need to be expanded to serve as a feeder road to this new highway. Ensuing years of residents’ protests were ignored and construction began in 1956. Completion of the 1948 Druid Hill Expressway and 1963 Jones Falls Expressway resulted in the widening of Auchentoroly Terrace and Druid Park Lake Drive. Two-lane, park-front residential streets became dangerous five-to-nine-lane-wide highways. These expressways literally paved the way for white flight while cutting off the surrounding working class African American and Jewish neighborhoods from the park.

Local residents deserve priority access to Druid Hill Park. For the first time in over 50 years pedestrians, wheelchair riders, and bicyclists can now safely cross the Jones Falls Expressway thanks to the Big Jump shared-use path. More work needs to be done, but the Big Jump is a step in the right direction towards reconnecting our neighborhoods with Druid Hill Park.

Read more about the history of highway development and the Big Jump at Graham Projects: https://grahamprojects.com/2018/08/the-big-jump/

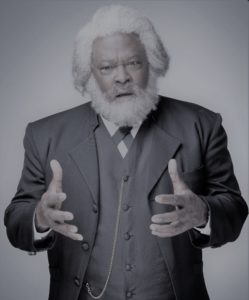

Graham Coreil-Allen is a Baltimore-based public artist and organizer working to make cities more inclusive and livable through public art, radical walking tours, and civic engagement. Coreil-Allen received his MFA from Maryland Institute College of Art and has created projects for numerous spaces, places and events; including the The Deitch/Creative Time Art Parade, Eyebeam, The Baltimore Museum of Art, Washington Project for the Arts, Arlington Art Center, VistArts, Artscape, Transmodern Festival, Current Space, ICA Baltimore, RedLine, Arlington Public Art, Light City, Baltimore City, and the US Pavilion at the 13th International Venice Architecture Biennale.

The public artist lives and works on Auchentoroly Terrace in West Baltimore where he also serves as the communications specialist for the New Auchentoroly Terrace Association. Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed on our blog do not necessarily reflect the views or position of Maryland Humanities or our funders.