The Maryland Women’s Heritage Center and Museum (MWHC) is one of is a recent recipient of one of Maryland Humanities’ Voices and Votes Electoral Engagement Project Grants. Tomorrow (January 28) at 4:00 p.m., MWHC hosts a virtual panel, “The Next 100 Years: Continuing the Work of our Maryland Foremothers,” to explore issues and strategies for promoting a stronger, more equitable democratic process. Jean Thompson, Volunteer Researcher at MWHC, writes about women’s current and past civic engagement.

Vice President Kamala Harris has paid homage to suffragists and voting rights activists for their valor and toil. A full century after the passage of the 19th Amendment confirmed women’s right to vote, the suffrage movement informs the historic moment of Harris’s inauguration and the future for women in political participation. Voter mobilization and political action by women, especially women of color, have been credited with making Harris America’s first female vice president.

“Women achieved political power through civic engagement, and that is a powerful legacy of the suffragists that we must always remember,” says Diana M. Bailey, executive director of the Maryland Women’s Heritage Center. “The suffragists never intended to win access to the ballot and then set that power on a shelf to gather dust.”

As we train our sights on the next 100 years, one lesson of the suffrage movement is that civic engagement and political involvement are as essential to the exercise of democracy as the ballot itself. How will women shape the nation’s evolving and uneasy democracy into a “more perfect union”? What barriers must be overcome to address women’s agendas for equity, family, health, education, and response to the pandemic, which has forced women from the workforce in disproportionate numbers? The call to action is clear.

“It is important for my voice [to be heard] as a Black mother, social worker, and advocate to overcome the unequal gender norms that plague our democratic processes,” says Jocelyn Route, Bladensburg, Md., Ward 1 Council Member, and a 2020 newcomer to public office. “I could only make true change by pulling from my ancestors’ bravery and strength to continue to fight for human rights for all, effective and transparent government, and equality. I am motivated by my children who ask me to change unfair practices. I share with them ‘I don’t have that much power, but I can make a difference.’ I truly work hard for them, longing to make life a little bit better.”

Council Member Route will be among the panelists discussing women’s civic involvement during The Next 100 Years: Continuing the Work of Our Maryland Foremothers, an online conversation January 28, 2021, from 4pm to 5:30pm. Joining her will be Elaine Apter, First Vice President and Program Chair of the League of Women Voters of Maryland; Alice Giles of the League of Women Voters, Howard County; Jacqueline Gray, Diversity Chair, AAUW Maryland; and Odette Ramos, Baltimore City Councilwoman, District 14. The conversation will be moderated by E.R. Shipp, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, author, and associate professor in the School of Global Journalism and Communication at Morgan State University.

This virtual event, sponsored by the Maryland Women’s Heritage Center with support from Maryland Humanities and The Voice and Votes Electoral Engagement Support Grant, is nonpartisan, free, and open to the public. Register here.

Ever since St. Mary’s County landowner Margaret Brent asked the Maryland General Assembly for the right to vote in 1648, Maryland women have fought for a rightful place in American democracy. In what became a multigenerational quest to gain what Brent was denied, suffragists employed sophisticated strategies for galvanizing support for voting rights. By 1920, farmers’ wives had gathered to hear suffrage speeches on the Eastern Shore, Black clubwomen on Baltimore’s Druid Hill Avenue had taught voter preparation classes at the city’s Colored YWCA, hikers had leafleted along byways in Western Maryland counties, marchers (some pushing baby strollers) had paraded in downtown streets, picketers had stood as sentinels in front of the White House in Washington. Many suffragists had overcome derision, prejudice, and sometimes violence in their quest for access to the ballot.

Within two years of the 19th Amendment’s passage, Harford County voters elected Mary Eliza Risteau to represent them in the Maryland House of Delegates, a first for a woman. In growing numbers, women began running for office. For others, the 19th Amendment did not deliver, an uncomfortable truth that still reverberates today: Through voter suppression, many Black citizens across the South were denied the ballot, and only through continuing political action did they gain voting rights in 1965. The 19th Amendment did not provide universal suffrage for women: Native American women began receiving U.S. citizenship and the right to vote in 1924, and Chinese immigrants in 1943.

Yet here we are: Today, a woman who is African American, Asian American, and a descendant of immigrants has an office in the West Wing. The challenge for American women now is to ensure that all citizens – and the next generation of women – understand civic responsibilities including voting, thinking critically about legislation, advocating for change, understanding others’ viewpoints, voting mindfully, and leading. The technology and tools of voting rights and activism change but the fundamental need for an active and informed electorate endures.

“My grandmother, Margaret L. Smith, a sharecropper who grew up in Council, N.C., influenced my work ethic and reminded me that if ‘I want something done the right way, I must take the lead and encourage those around me to join in…,’” said Council Member Route. “I don’t take my grandmother’s sayings lightly because I have witnessed power in numbers, and she is the brave Black woman that helped shape who I am today.”

Voices and Votes Electoral Engagement Project was funded by the ‘Why It Matters: Civic and Electoral Participation’ initiative, administered by the Federation of State Humanities Councils and funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed on our blog do not necessarily reflect the views or position of Maryland Humanities or our funders.

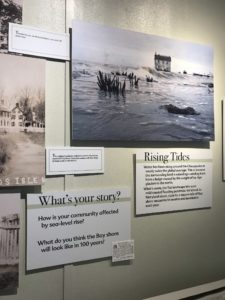

A: Maryland H2O was the umbrella initiative that brought together Maryland Humanities’

A: Maryland H2O was the umbrella initiative that brought together Maryland Humanities’  Q: How did you come up with the idea for Maryland H2O?

Q: How did you come up with the idea for Maryland H2O? Q: How was the program unique in contrast to other programming Maryland Humanities has done? What was special about it?

Q: How was the program unique in contrast to other programming Maryland Humanities has done? What was special about it? Q: What did Maryland H2O teach you about our state?

Q: What did Maryland H2O teach you about our state? Q: What were some of the best reactions from partners and event attendees on Maryland H2O?

Q: What were some of the best reactions from partners and event attendees on Maryland H2O?