Like most people, I try to be a good steward of the planet: I try to recycle, I think about sustainability and environmental destruction, and I am trying to understand the social roots of environmental problems. I do care about the environment but – like most people – I am not actively involved in nor do I really understand what it means to practice the art of daily ecojustice. This is a new area of study for me and through reading and studying the work of Dr. Rita Turner, I am learning about what it means to be personally involved in and connected to trying to do the hard work to save our planet. I have also learned how to share and teach this work to others. If activism, according to Alice Walker, is our rent for living on the planet then practicing the art of daily ecojustice is the work we do to keep the lights on for the next generation.

Environmental justice cultural studies is a relatively new area of study that combines the fields of environmental history, critical legal studies, social science, ethnic studies, women’s studies, cultural geography, and other forms of cultural criticism and as such, practitioners have been actively working to take this information into the K-12 classrooms.[1] As we begin to start preparing for Earth Day 2016, I sat down with writer and ecojustice activist Rita Turner to discuss her new book, Teaching for EcoJustice—which focuses on a curriculum that she developed to take ecojustice activism into humanities-based educational settings.

Kaye Whitehead: Why did you decide to write this book?

Rita Turner: I think this book was motivated by fear for the world, and by love for it. I look at the serious environmental and social problems we’re facing today, and I’m terrified and angry. But I also feel so much love for the land, for other living beings, and for people. I want to help young people to connect with the love that we as humans can inherently feel for and desire from the world around us, and I also want them to learn to think very critically about why we treat the world the way we do and what the alternatives could be for a better, more just, more abundant and healthy world.

Despite all the terrifying problems looming over us in the world today, I feel that, as a society, we rarely have real conversations about the roots of environmental and social issues. Our behavior is motivated by our belief systems, our attitudes, our values – and these belief systems too often go unexamined. How do we see the world around us? What do we believe our relationship should be, to other people, to other species of animals, to the land? Our culture encourages and maintains certain answers to these questions, whether we realize it or not. And when we look at these culturally reproduced beliefs, we find that they’re often based on hidden assumptions and hierarchies of value, about who is more or less important.

I feel it’s essential that we begin to incorporate into our public lives real strategies for analyzing and reformulating the underlying beliefs and assumptions that have produced such damaging consequences in the world. Schools and other educational sites are some of the best places to begin. I also think we owe it to the students we are teaching to give them a clearer view of their own culture and of the roots of the problems that they will have to tackle in their lifetimes. Schools should be places that encourage sustainability and justice, not places that simply reproduce the status quo.

So I started designing and testing curriculum materials that help students take a closer look at their relationship to the larger world around them, at their own cultural belief systems, and at the effects of those beliefs as they play out in our actions. I spent years designing and testing the materials, and I’m so excited that now they’re collected into a form that high school and college teachers can use in their own classrooms.

KW: Which writers inspire you?

RT: David Abram is a beautiful writer whose ideas have also been extremely influential to me in my own work. Other sources of inspiration come from far and wide! Wisława Szymborska, William Faulker, Terry Pratchett, Mark Doty, Alice Walker, bell hooks, Virginia Woolf… I could go on!

KW: What does being a writer mean to you?

RT: I think of myself as an educator more than as a writer, but in some ways for me those are the same. Language has so much power – it can be used to mask truths or reveal them, to open us up to connections or isolate us from others. I want my writing to be a force for connection, and for unflinching examination of ourselves and our world. I want it to push us to look at things we’re not used to seeing.

KW: What book do you wish you could have written?

RT: Oh goodness, The Spell of the Sensuous by David Abram has made such an impact on me. I admire David Abram’s perspective.

KW: You refer to yourself as a scholar/writer – can you explain what this means to you?

RT: It may be obvious by now that I think critical examination of our culture is so very important. To me this means blending scholarship and writing and education. There shouldn’t be just a handful of people in the world who have closely examined the cultural belief systems that influence all of us each day – we should all be doing that. My scholarship, to some extent, is about finding ways to make such examinations part of public life and educational life.

KW: What writing advice do you have for other aspiring authors?

RT: Write for those you love. Write to give something to the world for their sake, to make their futures better, or to honor them, or to share what they’ve taught you. Be moved by what the world has given you.

KW: What advice would you give to your younger self?

RT: I guess I would say keep following your path wherever it takes you! It will all add insights and experiences to who you become in the future. And give yourself as fully as you can to your work and your loved ones and the world.

KW: Tell us about the cover and how it came about.

RT: The book cover was a collaboration with my terrific editor. I’m very happy with the image. I want the book to help move us toward healthier, more just, and more reflective relationships with other beings, and I hope that’s captured in the cover image. There are possibilities for living more collaborative and more respectful lives, shared with other people, other creatures, and the land. We should be finding those possibilities.

About the Writer: Rita Turner, Ph.D., is a Lecturer at the University of Maryland Baltimore County, where she studies the cultural roots of environmental and social problems, and develops curricula to analyze these cultural roots through education. She received her PhD in Language, Literacy, and Culture from the University of Maryland Baltimore County in 2011. Prior to her graduate studies, Dr. Turner taught high school English in a Baltimore City public school and ran a national nonprofit environmental advocacy organization for high school and college students. She is a resident of Baltimore City, where she also works on issues of food justice, environmental racism, and urban agroecology. Teaching for EcoJustice: Curriculum and Lessons for Secondary and College Classrooms is her first book. Read more about the book and find out how to purchase a copy on the Teaching for EcoJustice website.

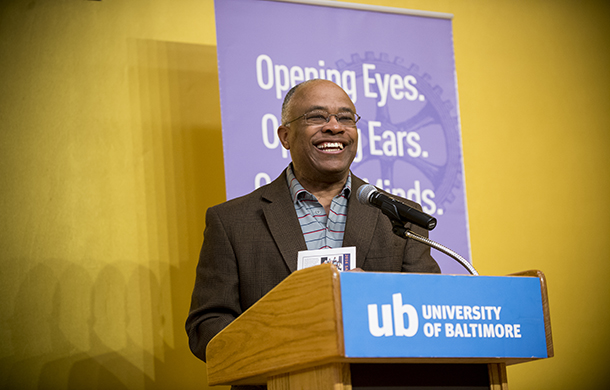

About the Interviewer: Karsonya “Kaye” Wise Whitehead, Ph.D. is Assistant Professor, Department of Communication at Loyola University Maryland and the Founding Executive Director at The Emilie Frances Davis Center for Education, Research, and Culture. Her new anthology, RaceBrave, was published in March 2016.

[1] For more information on environmental justice cultural studies, see http://culturalpolitics.net/environmental_justice/introduction

Duke Ellington is considered one of America’s greatest composers. Born in 1899 in Washington, DC, Ellington was an incomparable showman who was one of the greatest composers of the twentieth century with a career that spanned over fifty years. With over 300 compositions over his lifetime, Ellington was posthumously awarded a special Pulitzer Prize “commemorating the centennial year of his birth, in recognition of his musical genius, which evoked aesthetically the principles of democracy through the medium of jazz and thus made an indelible contribution to art and culture.”

Duke Ellington is considered one of America’s greatest composers. Born in 1899 in Washington, DC, Ellington was an incomparable showman who was one of the greatest composers of the twentieth century with a career that spanned over fifty years. With over 300 compositions over his lifetime, Ellington was posthumously awarded a special Pulitzer Prize “commemorating the centennial year of his birth, in recognition of his musical genius, which evoked aesthetically the principles of democracy through the medium of jazz and thus made an indelible contribution to art and culture.” Gwendolyn Brooks was an African-American poet whose works illuminated the

Gwendolyn Brooks was an African-American poet whose works illuminated the Ernest Hemingway was one of the greatest American literary figures of the twentieth century who continues to influence modern literature with his trademark style of simple yet perceptive prose. Born in 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, Hemingway’s experiences abroad as a foreign correspondent and as an ambulance driver for the Red Cross during World War I greatly influenced his literary works, such as A Farewell to Arms. Hemingway’s hobbies, including big game fighting, bull-fighting, and deep-sea fishing, also influenced his writings, particularly his novel The Old Man and the Sea which earned him the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1953 and led to the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954.

Ernest Hemingway was one of the greatest American literary figures of the twentieth century who continues to influence modern literature with his trademark style of simple yet perceptive prose. Born in 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, Hemingway’s experiences abroad as a foreign correspondent and as an ambulance driver for the Red Cross during World War I greatly influenced his literary works, such as A Farewell to Arms. Hemingway’s hobbies, including big game fighting, bull-fighting, and deep-sea fishing, also influenced his writings, particularly his novel The Old Man and the Sea which earned him the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1953 and led to the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954.