American Brewing Throughout the Years

By Emma Schrantz

University of Maryland

With Meagan Baco

Preservation Maryland

Beer brewing in the United States began almost as a necessity. During the early days of the United States, fermented drinks like beer and ciders were safer to drink than water. The boiling and fermentation process killed disease-causing organisms, which prevented serious illness like cholera

As such, the drink became ingrained in the social circles in America, with Native American tribe and Colonial populations embracing the need for fermented beverages in society. Beer and other alcoholic drinks like rum and cider became woven into the social fabric of the Thirteen Colonies. To meet the demand of colonial cities, local breweries began popping up throughout the East Coast. The first brewery in the State of Maryland was established in Annapolis as in 1703: this laid the groundwork for what has become a strong industry in the Old-Line State even into the present day.

Many of the Founding Fathers had a soft spot for beer – George Washington himself was known to brew beer and enjoy American-made Porters. Brewing in colonial days was a female-driven industry, with much of the production happening in the home. Even Martha Washington managed the home brewing at her husband’s estate. Once the American Revolution broke out, the import of alcohol from England became incredibly expensive. American beer became a symbol of American independence – and has remained one of the most recognizable elements of American culture since its founding.

During the 1800s, German immigrants had an especially large impact on the social side of brewing, carrying with them a rich brewing heritage. They introduced America to the lager style and the rich social tradition of the German Biergarten. This cultural shift increased the popularity of beer in America, and the number of breweries swelled to more than 4,000 by the year 1873. However, this growth was very quickly stifled. Around the turn of the 20th Century, many Americans saw alcohol as a so-called “demon drink”. The Temperance Movement sought to crush the exploding brewery industry. Many ‘prohibitionists’ blamed the social woes plaguing American cities on the over-consumption of whiskey and other hard spirits, claiming that they posed a serious threat to the country’s fledgling political system.

The Movement’s efforts were successful in demolishing the brewing industry. Home-brewing was almost completely eliminated, and many women became disassociated with the practice. Breweries shuttered around the country at a rapid pace. Finally, the United States enacted Prohibition with the ratification of the 18th Amendment in 1919. Prohibitionists celebrated, expecting an improvement in the ‘moral compass’ and order in American cities. However, Prohibition did exactly the opposite – protests and riots broke out across the country, and an entire new industry of bootleggers and speakeasies developed. Some companies even sold malt products disguised as baking ingredients in order to keep American brewing afloat. The backlash was so strong that the U.S. Government eventually ratified the 21st Amendment, which repealed Prohibition in 1933.

Despite the repeal, American brewing took nearly 75 years to recover from the effects of Prohibition. Homebrewing was not legalized in the 21st Amendment, so Americans relied on breweries for their beer. Advancements in refrigeration, advertising, manufacturing technology, and distribution networks during the 20th Century enabled beer and other beverages to be canned and shipped thousands of miles away. Large brewing companies like Anheuser-Busch were able to weather prohibition due to their vast distribution networks and support of the American Armed Forces. These breweries succeeded due to the production of one or two styles, made with inexpensive ingredients and shipped all around the country. Larger breweries were able to purchase and consolidate their competitor’s businesses, following the trends in other industries across America. Just like Coke and Pepsi, brands like Budweiser and Miller became household staples around this time.

By the 1960’s, this rapid consolidation nearly decimated the brewing industry. No longer did Americans need to go to their local breweries or taverns to grab a beer. They could buy cans of beer, produced thousands of miles away, in the comfort of their own homes. The economic impact was so dire that just six brewing companies gained control of over 90 percent of the entire beer market. However, the cultural revolution of Craft Brewing rose to challenge the “Big Beer” companies.

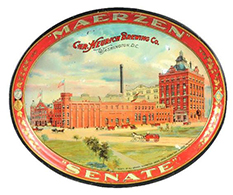

One of the last breweries to hang on during this period of consolidation was the Christian Heurich Brewing Company that was located on the Potomac River on what is now the site of the Kennedy Center. The Heurich Brewing Company was in operation from 1872 through 1956 and during its height of production at the turn of the century, it was the second largest employer in Washington D.C. – apart from the Federal Government. The Heurich mansion is now run as a historic house museum and has brought back some historic recipes of Heurich in partnership with DC Brau Brewing. DC Brau has the distinction of being the first brewery to open since Heurich’s closing –they tapped their first keg in 2011.

With the passage of HB 1337 in 1977, home brewing was again made legal, and brewers began experimenting with craft brewing and playing around with styles and ingredients in their homes. Craft brewers are generally more concerned about the quality of the beers, as well as the social culture of beer production and consumption.

Here in Maryland, the Brewers Association advocates for the craft beer community including issues of production and distribution limits for over 70 Maryland-based breweries. Together, the brewers have a $637.6 million impact, support 6,541 jobs with $228.3 million in wages and $53.1 million in state and local tax revenue.

Breweries have also proven their commitment to the spirit of Maryland pride by being a part of great partnerships, like the sour table beer collaboration between the National Museum of Civil War medicine and Flying Dog brewing known as Sawbones – and the recent Light City collaboration “Lumen Ale” between Baltimore Office of Promotion of the Arts and Brewer’s Art. Guinness is also committing to Maryland by opening the first Guinness Brewery on U.S. Soil since 1954 in Elkridge, Maryland in the Patapsco Valley State Heritage Area.

If reading this made you thirsty, one of our favorite local Baltimore breweries is Peabody Heights Brewing on the site of a former Orioles stadium that has a great collection of vintage O’s photographs in the tap room.

Meagan Baco is the Director of Communications at Preservation Maryland. She is also the co-founder of Histpres, a national job board for the historic preservation field, and has spoken about the young preservation movement and job market at conferences across the country. Meagan also serves on the board of the Old Greenbelt Theatre.

Emma Schrantz is pursuing a Master’s degree in Architecture and Historic Preservation at the University of Maryland. She writes about the intersections between the craft brewing industry, historic preservation, and community development.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed on our blog do not necessarily reflect the views or position of Maryland Humanities or our funders.

Angela R. Hooks

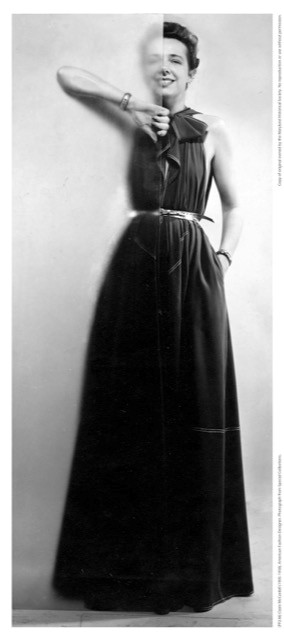

Angela R. Hooks Take, for example, the pale pink evening gown designed and worn by Claire McCardell from the 1940s. Claire McCardell (1905-1958) is a Frederick-born fashion designer who challenged the then-standard practice of copying French couture designs. Instead, she created functional, easy-to-wear dresses that helped to shape “the American Look”. McCardell believed that American women like her, wanted to be comfortable while looking good. As she put it, why wouldn’t other women want to wear the clothes that she herself wanted to wear?

Take, for example, the pale pink evening gown designed and worn by Claire McCardell from the 1940s. Claire McCardell (1905-1958) is a Frederick-born fashion designer who challenged the then-standard practice of copying French couture designs. Instead, she created functional, easy-to-wear dresses that helped to shape “the American Look”. McCardell believed that American women like her, wanted to be comfortable while looking good. As she put it, why wouldn’t other women want to wear the clothes that she herself wanted to wear?