Breai Mason-Campbell watched as the teen girls at Mercy High School took selfies wearing lapas—colorful West African skirts worn in dancing—and headdresses. Her colleague, Amaniyea Payne, choreographed the high school girls in a piece about Frederick Douglass, after Mason-Campbell and Payne joined them in watching a documentary created by a Mercy alumnus and looking at old photographs of him. (“This this man would have been a GQ model, I’m telling you,” she says as an aside.)

“They have such a sense of dignity, you know, pride and excitement about their own culture,” Mason-Campbell tells me.” There’s moments that, I’m just like, ‘Oh, look, it works.’”

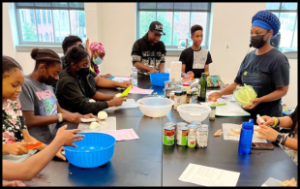

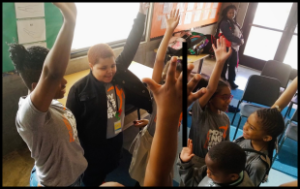

Dignity and cultural memory are key to Moving History, which Mason-Campbell originally founded as a dance performance troupe under the name Guardian Dance Company. The organization now bills itself as “Kinetic African American History” and expanded the organization’s work to have a broader and more immersive focus to fulfill the mission of “teaching the story of African-American people.” Along with dance, activities include cooking African American cuisine, creating visual art, and playing instrumental and vocal music.

“I wanted my community to have a greater measure of dignity,” a goal that Mason-Campbell said stemmed from reflection on personal experience. “I really had a lot of questions about the causes of poverty, like, the cycles of violence that I had been a party to growing up in Baltimore,” she says. “ I buried so many friends in high school. You know, it was like you hear about it on the news. But like, I’m a real person in one of those stories.”

Mason-Campbell reveals that she lost her own boyfriend to gun violence after her high school graduation. She could name someone she knew who died for each year in high school. “These weren’t people who were distant friends. It‘s was my group of friends, like my walk-around, my go-to-the-basketball-court friends, my hang-out-outside-and-talk friends.”

She sought the answers to these questions about root causes of violence and poverty in college and graduate school. Mason-Campbell earned a Bachelor’s degrees in both Religion and Geography & Urban Studies from Temple University in 1999. She then received her Master’s Degree from Harvard Divinity School with a focus in African American Social Ethics, with a thesis on Hip-Hop as a religious and moral touchstone for African American youth.

“I started to learn about structural racism and structural oppressions.” Mason-Campbell outlines sixteen years of working in Sandtown after school. “Over the course of those years, the company was starting to operate even without a name but I had come to correlate a sense of dignity, a sense of identity with a healthier community.” Discussion of race is connected to self-esteem, posits Mason-Campbell. “But when we talk about race and self-esteem, then it’s like, oh, this is political, you know, we’re not having this conversation or whatever.”

Mason-Campbell compares what she tries to provide to Hebrew School. She mentions she has friends who are all different branches of Judaism, or non-observant, but they have the shared experience. “That depth of connection with history, of purpose and culture, really seems to do something buoyant for people. And I wanted my community to have that kind of buoyancy, that sense of belonging, that sense of gravitas, of the importance of self and the importance of community and the importance of legacy.”

Mason-Campbell works directly with students, as opposed to only performing for them, because “that’s the way that knowledge passes in our community.” She talks about family recipes. “This is a serious thing around here, how you make the macaroni and cheese. It must be a part of memory.”

Mason-Campbell worked with two students for ten years, on the Lindy Hop, the 1928 dance. “Though it’s a dance from Harlem, it’s become super dominated on the international competition stage by Sweden, because Sweden had all this money to come and take our Lindy Hop greats and bring them over there to teach,” she says. “And you know, because the way Jim Crow worked here, Lindy Hop wasn’t preserved.” She references Norma Miller and Frankie Manning, Black Lindy Hop dancers who didn’t reach the same height of fame as Astaire. “Fred Astaire can move to California and open a studio, right? Two black dancers can’t do that. We, in fact, don’t even know their names because of Jim Crow.”

Mason-Campbell’s two students would attend the international Lindy Hop competition year after and lose to Swedish dancers. In 2019, she had the opportunity to send them to Lindy Hop camp in Sweden. “We pushed and pushed and pushed,” she tells me. “They won. First place. From first grade to twelfth grade is how long it took. But we did it.”

Inequity clutches to every field, and the nonprofit sector is not absolved. Nonprofit Finance Fund reports that forty-one percent of white-led nonprofits received 50% or more unrestricted funds in FY2021 as compared to 26% of BIPOC-led organizations. Mason-Campbell has to maintain another job to support her work with Moving History. “With education classes for kids, or, you know, training for teachers, or whatever we’re doing, communication with our supporters, online stuff, all of that stuff can’t happen without funding.”

Mason-Campbell states that without the $10,000 Strengthening the Humanities Investment in Nonprofits for Equity (SHINE) grant from Maryland Humanities, she wouldn’t be able to keep two members of her staff aboard. Payne and Sonya Kumar serve as the organization’s Arts Program Coordinator and Administrator, respectively. Mason-Campbell relies on Kumar to communicate with supporters and complete digital work. Payne—who also choreographed the Frederick Douglass piece—liaises with the sites where Moving History performs and educates. “There just wasn’t money to pay people,” Mason-Campbell says. “And me paying them out of pocket, which I have again and again, it’s just not sustainable. I’ve got three kids, you know?”

Mason-Campbell expresses a wave of relief when she learned Moving History received the SHINE funding. “Knowing that I could pay payroll, and we would have more money left was a relief because sometimes we pay payroll, and that’s everything. And then I’m like biting my nails,” she confesses. “The fact that we pay payroll, and then there was still money, which meant I could go into another payroll with money just to pay staff? It’s like such a weight off my shoulders.”

Mason-Campbell places Moving History in the landscape of Maryland, what she calls a “forerunner in pushing for social justice,” especially in the national climate with ban on discussing race, gender, or sexuality in the classroom. “This is just another way we can stand for justice,” she says. “Y’all might think that you’re going to say, we don’t say race, or we don’t say gay, whatever else, you decided to try to silence people about to try to create some kind of real false sense of homogeneity and maintain your power structure the way it exists,” she adds. “We’re saying, ‘No. We’re going to center discussions about our cultural heritages. We’re going to center these histories and the learning of these cultures, their preservation, and their practice.’”