Preservation Maryland, one of the country’s largest and most active historic preservation and public history organizations, is a recent recipient of one of Maryland Humanities’ Voices and Votes Electoral Engagement Project Grants. The organization will use the $2,000 grant to expand the organization’s Ballot & Beyond women’s history project to continue to tell the complex story of Maryland’s suffragists – some of the country’s first voting rights activists – in an online multi-media website. Project leader Meagan Baco, Director of Communications at Preservation Maryland, shares their experience in this guest blog post.

For many Marylanders, the cacophony of 19th Amendment 100th Anniversary events in 2020 were a (re)introduction to the complexities of women’s suffrage movement. With Ballot & Beyond, Preservation Maryland is not shying from the difficult history of women’s suffrage and we are working into 2021 to create new educational resources about this voting rights campaign.

The project has been enlightening, and even jarring: White suffragists actively spoke out against black enfranchisement and while the movement was chock full of lesbian and gender-diverse leaders, those identities and relationships are largely erased. Maryland was not one of the states ratify the 19th Amendment in 1920, in fact, our legislature waited until 1958. To be sure, Maryland’s role in the fight for women’s suffrage was far from perfect and previous over-simplifications were never accurate and are no longer adequate. We must tell the full story. Preservation Maryland is honored to be part of the work to tell the full story of Maryland’s suffragists and their complex legacy.

Here are just some of the stories on Ballot & Beyond:

Mary Bartlett Dixon of Easton, Maryland was in the thick of suffrage work as a leader in the Talbot County chapter of the Just Government League. She also wrote regularly for the Maryland Suffrage News and edited a regular column for The Baltimore Sun entitled “What the Suffragists Are Doing.” In 1913, Dixon was one of just a handful of women who met with President Woodrow Wilson shortly after his inauguration to ask him to support a constitutional amendment enfranchising women — which he did not do at the time. When Wilson was re-elected in 1916, suffragists took their fight to his doorstep. Harrowing stories of cruel treatment at prisons threads through the story of the women’s suffrage movement, yet Dixon joined the White House non-violent pickets and was arrested with 40 other women in the winter of 1917.

Dixon is only one of the leaders featured in Ballot & Beyond, which commemorates Maryland’s suffragists and shows the impact of their legacy on more contemporary female leaders in Maryland. The grassroots petitions and letter-writing campaigns employed by suffragists are now a mainstay for citizen advocates. Moreover, suffragists like Dixon are also credited with staging those first protests in front of the White House – an enduring form of political activism.

There are fifty-five episodes online now crafted by thirty-one researchers, writers, editors, and readers. Commenting on the task of selecting women to highlight, Diana Bailey, Executive Director of Maryland Women’s Heritage Area a partner of the Ballot & Beyond project [and another Voices and Voters Electoral Engagement Project Grantee], explained, “We are especially concerned with representing the critical intersectionality of race and gender in the history of the suffrage movement as new documentation comes to light.” The cohort of women includes African American women, women of a wide array of religions and gender expressions, and women from urban and rural communities across Maryland.

The grant from Maryland Humanities supports video companion pieces to the oral biographies. The videos feature historic images and newspaper clippings of Maryland women and summarize the strategies they used to ensure a place for women in the civic arena. The project also utilizes a new wave of suffrage scholarship are illumining the decisive work of African American women as voting rights advocates while they also contended with sex- and gender-based harassment and racism.

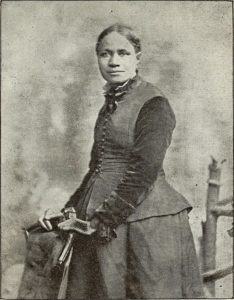

Francis Ellen Watkins Harper, born free in Baltimore in 1825, is a legendary civil rights activist who saw the intersection of the fight for abolition and suffrage. Harper, a contemporary of Frederick Douglass, was a published poet and author who campaigned around the country for temperance, abolition, and women’s rights. In an attempt to create social unity after the American Civil War, American Equal Rights Association members like Harper believed it was the right time to integrate gender, race, and class-based advocacy in a broad push for equality. Harpers integrated goals and ideal was largely unheeded and the suffrage movement was highly segregated. Across the country, the suffrage movement was largely segregated (from within and without) spurring parallel white and black suffrage and civil rights groups. For example, Estelle Hall Young founded the Colored Women’s Suffrage Club in Baltimore City in 1915.

Many suffragists took great personal risk in joining multi-state “hikes” across the East Coast and through Maryland to garner new recruits for their cause – and keep the campaign in the media through spectacle. And it was! Women walking outdoors unaccompanied by a male companion was enough to get people talking – mostly by hurling sex- and gender-based threats. Yet, they endured. In June of 1914, a group of Maryland suffragists took a two-week hiking campaign through Garrett County.

Maryland Suffrage News that as the hikers drew curious audiences each woman would be assigned a role: two to hand out literature, two to hand out membership cards, and everyone to speak in turn. This strategy earned the Just Government League over 800 new members and had quite an impact on the individual women as well, previously socially confined to the private sphere of the home. Some suffragists even drove cars!

After ratification in 1920, Black women like Augusta Chissell carried the torch of the suffrage movement into voting action – African American women stayed highly-engaged in civil rights work because unlike white women, Black women still faced legal voting restrictions until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which barred racially discriminatory voting practices. Chissell wrote a column at The Baltimore Afro-American, entitled “A Primer for Women Voters.” Readers wrote in with questions like “What is meant by party platform?” and “Where may I go to be taught how to vote?” – essential information for any would-be voter provided only thanks to the enduring efforts and engagement of female civic leaders well-into the 20th Century.

With support from Maryland Humanities, Preservation Maryland will also create and release biographical videos about the following women, in addition to Dixon and Harper:

- Margaret Brent (c. 1601-c. 1671) a 17th Century Landowner and Suffragist

- Nannie V. Melvin (1865-1942) Eastern Shore Suffrage Leader

- Sadie Jacobs Crockin (1880-1965), a Jewish-American suffragist in Baltimore

- Mary Risteau (1890-1978) First Maryland Women Elected to State House & Senate

- Catherine Sweet (ca. 1896), a foiled early female voter in Western Maryland

All Ballot & Beyond videos (to be released January 2020 through March 2020), on-demand podcasts, and historic photographs are available at: ballotandbeyond.org.

Ballot & Beyond is powered by Preservation Maryland and the organization’s podcast, PreserveCast, with support from Maryland Humanities, Maryland Historical Trust, Maryland Women’s Heritage Center, and Gallagher Evelius & Jones Attorneys at Law. VVEEP was funded by the ‘Why It Matters: Civic and Electoral Participation’ initiative, administered by the Federation of State Humanities Councils and funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed on our blog do not necessarily reflect the views or position of Maryland Humanities or our funders.