Celebrating Poetry Month

Two Poets and Their Diaries: Alice Dunbar-Nelson and Gwendolyn Bennett

By Angela R. Hooks, Ph.D.

Flipping through my diary I noticed I had composed a poem. The poem had been rewritten three times with words and lines deleted and stanzas revised. To create the poem, I followed an exercise in Richard Hugo’s book Triggering Towns that required choosing five nouns, verbs, and adjectives for a list. The poem had to include four beats to a line, six-line stanzas, three stanzas, two internal and one external slant rhymes per stanza, two end stops per stanza, and clear grammatical sentences that make sense. The poem must be meaningless. According to my diary, my poem took one week to complete and needed additional wordsmithing and less beats. As a diary-keeper of more than three decades, writing in my diary has augmented from space for reflection into a space to hone my craft. For many writers and poets, the diary manifests by way of a springboard to produce poems from experiences, observations, and emotions. Rereading the poem and the marginalia notes about the poem reminded me of the diary pages of two American poets: Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1875-1935) and Gwendolyn B. Bennett (1902-1981) and the legacy they left for other poets, writers and diary-keepers.

I have read, studied, and examined Give of Each Day; The Diary of Alice Dunbar-Nelson, published diaries, and the unpublished diaries of Bennett, housed at Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Book Division. I discovered despite the busy lives they led as educated, middle-class professionals entrenched in social activism, including education, for the black race, both their diaries served as a writer’s workshop to hone their skills, create poems, and keep track of submissions.

The Poets

Gwendolyn Bennett was a Renaissance woman, who contributed to the arts as a painter, graphic artist, art professor at Howard University in Washington, DC, and in the literary world as poet, short-story writer, and editor and columnist of “Ebony Flute.” As a visual and literary artist, Bennett was a prolific poet known as the seed of the Harlem Renaissance. Bennett left a legacy of twenty-two poems that appeared in journals of the period: Crisis, Opportunity, Palms, and Gypsy and the Messenger. Additionally, other poems were collected in William Stanley Braithwaite’s Anthology of Magazine Verse for 1927 and Yearbook of American Poetry (1927), Countee Cullen’s Caroling Dusk (1927), and James Weldon Johnson’s The Book of American Negro Poetry (1931). She was and remains known for the poems “To Usward,” “Song,” “Lines Written at the Grave of Alexandre Dumas,” “Sonnet 1,” and “Sonnet 2.”

Alice Dunbar-Nelson was a prolific writer continuously producing and publishing varied forms of literature from 1895 to1931. She published her first book short stories and poems Violets and Other Tales at age nineteen. She wrote articles for Daily Crusader, the Journal of the Lodge, and black magazines like Age, Boston Woman’s Era and Boston Monthly Review and the Colored American. In 1899 she published another book of stories, The Goodness of St. Rocque and Other Stories. Her poems appeared in Crisis, Ebony and Topaz, Opportunity, Negro Poets and their Poems, Caroling Dusk, The Dunbar Speaker, and Entertainer, Harlem: A Forum of Negro Life and the Book of American Negro Poetry. She was and remains known for the poems “I Sit and Sew,” “Sonnet” and “April is on the Way.”

The Diary as a Writer’s Workshop

Dunbar-Nelson’s diary served as a writer’s workshop: a place that talks about writing, shows how to find time writing and how to use the diary as a springboard of ideas. Her diary is a space for the feminine voice that illuminates the stories of women. Dunbar-Nelson lived experiences were transformed from her diary into her creative work like Gwendolyn Bennett. Dunbar-Nelson wrote about the writing, its difficulties and her disappointments. For example, diary illustrates that she wrote in the kitchen by the window drinking a cup of tea; upstairs in the bed, plugging away at two o’clock in the morning, and in her office. On March 18, 1928, the diary had lapsed since February 9. Dunbar-Nelson first complained about the diary as “a weight on my heart to get it up to date. I carried it around to school and to the office. And like some inhibition, I could not bring myself to write. And tonight, when I ought to be in bed, the spirit moved me to straighten it out.” She was disciplined, writing daily.

In the diary, she recorded when she had written either a sonnet, poem, story or a novel. She also included publishing outlets where she submitted her work. The poet followed up in the diary recording whether the piece had been accepted for publication or rejected. Sometimes disclosing the prize money, if applicable. On Saturday, August 27, 1921 “finished a sonnet on Mme. Curie and sent to the [Philadelphia] Public Ledge for contest about “favorite woman of the ages” (62). Sunday, September 11, she penned that sonnet appeared in “to-day’s Ledger. That means I have a chance at the prize. Of course, it seems best of all the published ones, to me…” (72). While home writing in her diary, she noted that her sonnet was not a prize winner. She vented her disappointed and discouragement: she quoted Oscar Micheaux, a black filmmaker (1884-1951) “if you want to get anything across, it must be pure “bunk” absolute “bunk” which public will swallow, “hook, bait, sinker, line AND rod,” and then come up grasping for more” (September 18, 1921). At forty-six years-old the rejection left her discouraged “forty-six years old and nowhere yet” (77).

In her diary, she dutiful recorded her honorable mention of the poem “April is on the Way,” which she published under the name “Karen Ellison” for the Opportunity Contest. Her diary also confesses she reused “April is on the Way” for her monthly column “As in A Looking Glass.” She penned “At the bank Reilly quite excited over “April is on the Way” which I used for “As in A Looking Glass” as I felt too bum to do any column this week. Leslie quite excited over it too.” (218).

In April of 1930, she turned her emotions into writing sonnets. She wrote:

You did not need to creep into my heart

The way you did. You could have smiled

And knowing what you did, have kept apart

From all my inner soul. But you beguiled

Deliberately. Then flung my poor love by,

A priceless orange now. Without a sign

Of pity at the wreck you made. Smashed

The golden dream I’d reared. Then unabashed

Impaled the episode upon stupid epigram,

Blowing my soul thor’ smoke wreaths as you sneered a “Damn!”

She took her private feelings and usurped of the relationship and transformed her hurt into poetry. Her writing was not about confessing her secrets, but a way to allow her art to be free to go wherever it needed to go, and Marylin Schneider claims that “usually our pain comes out first” (ix). Within the diary, Dunbar-Nelson emerged as a writer who wrote deeply because her diary was safe until it was no longer safe. She was able to compose a poem about what she had experienced or imagined.

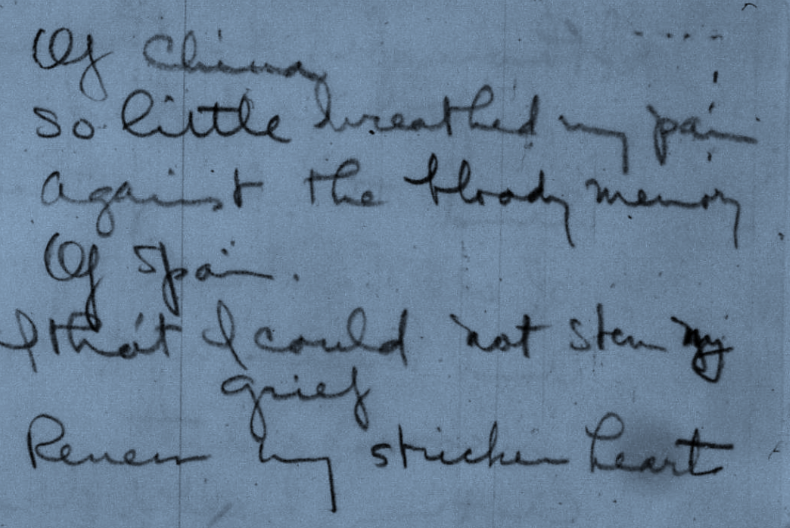

Even though Gwendolyn Bennett maintained three diaries, 1925, 1936 and 1958, her scrap paper and loose pages resemble a diary. Her writings on scraps of paper illustrate her creative process igniting her vision of writing poems. The thoughts on the scraps of paper happened at that very moment something happened and no other writing paper existed at that moment. When something happens that causes the diarist to contemplate the situation she must capture that moment on paper despite the size or form.

Not only did Bennett place her pain on the page, she used poetic techniques such as rhyme, metaphors and lines to create a poem. Her writing on loose pages and putting them in a folder instead of the trash can also indicate Bennett had hopes of reconstructing and publishing her poems.

Bennett kept a diary of handwritten poems written on scrap paper. Some scraps that Bennett penned poetry on were on the back of Cox, Nostrand and Gunnison letterhead. Cox, Nostrand and Gunnison was a lighting fixture company in New York, where Bennett worked. Others were scribbled on small scraps of torn or folded paper. She understood these poems were in progress, scribbling the words “poetry in progress” across the bottom of a piece of paper. Nevertheless, one poem reflects her experience at the cathedral in Paris in 1925 when her muse would not let her write poetry. These handwritten poems illustrate her emotionally freedom to once again write poetry that is “fluid with a breathing body” (Oliver 3). Other lines represent heart break of love.

These loose pages consist of more than twenty drafts of poems, some lines, stanzas and a few pages of research. Some poems have lines crossed out, words inserted, and appear as revised poems. Bennett’s process reflects Richard Hugo’s suggestions for rewriting poems in which the poet should “write the entire poem again” (37). Hugo claims, “If something goes wrong deep in the poem, you may have taken a wrong turn earlier. The next time through the poem you may spot the wrong path you took (37). Bennett’s markings indicate she reread her poems and when not on the right path changed words and played with syntax. Like me, Bennett followed the instructions of a more seasoned poet. One of Bennett’s handwritten poem emulates Elizabeth Bishop’s use of stress and unstressed syllables.

Dunbar-Nelson and Bennett were prolific poets of their time. Although devoted to the craft, neither bard published a complete body of poems in their lifetime. Yet the poetry Dunbar-Nelson and Bennett left behind, published and unpublished, voices the achievements and the legacy of Black American women poets making poetry apart of their culture.

Sources

Dunbar-Nelson, Alice Moore, and Gloria T. Hull. Give Us Each Day; The Diary of Alice Dunbar-Nelson. W.W. Norton & Company, New York. 1986.

Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Hugo, Richard. The Triggering Town, Lectures and Essays on Poetry and Writing. New York, London: WW Norton & Company, 1979.

Oliver, Mary, A Poetry Handbook: A Prose Guide to Understanding and Writing Poetry. New York, Harcourt, Inc.,1994.

Angela R. Hooks has defended her dissertation, and anxiously awaits her May 2018 graduation from St. John’s University to officially be Dr. Hooks. She teaches composition and literature. Her literary musings have appeared in African Notes, Vol. 40, Underground Writers, Balanced Rock: The North Salem Review of Art, Photography and Literature, Virginia Woolf Miscellany and Noise Medium.

Angela R. Hooks has defended her dissertation, and anxiously awaits her May 2018 graduation from St. John’s University to officially be Dr. Hooks. She teaches composition and literature. Her literary musings have appeared in African Notes, Vol. 40, Underground Writers, Balanced Rock: The North Salem Review of Art, Photography and Literature, Virginia Woolf Miscellany and Noise Medium.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed on our blog do not necessarily reflect the views or position of Maryland Humanities or our funders.