“I’m just a novelist.”

This was Ursula K. Le Guin’s repeated response at the University of Oregon in 2014 as people lined up to praise her with thoughtful, pleading questions. “How do you feel about the way gender is constructed in our society?” “What should we do now?”

“I put everything I had to say in my books.”

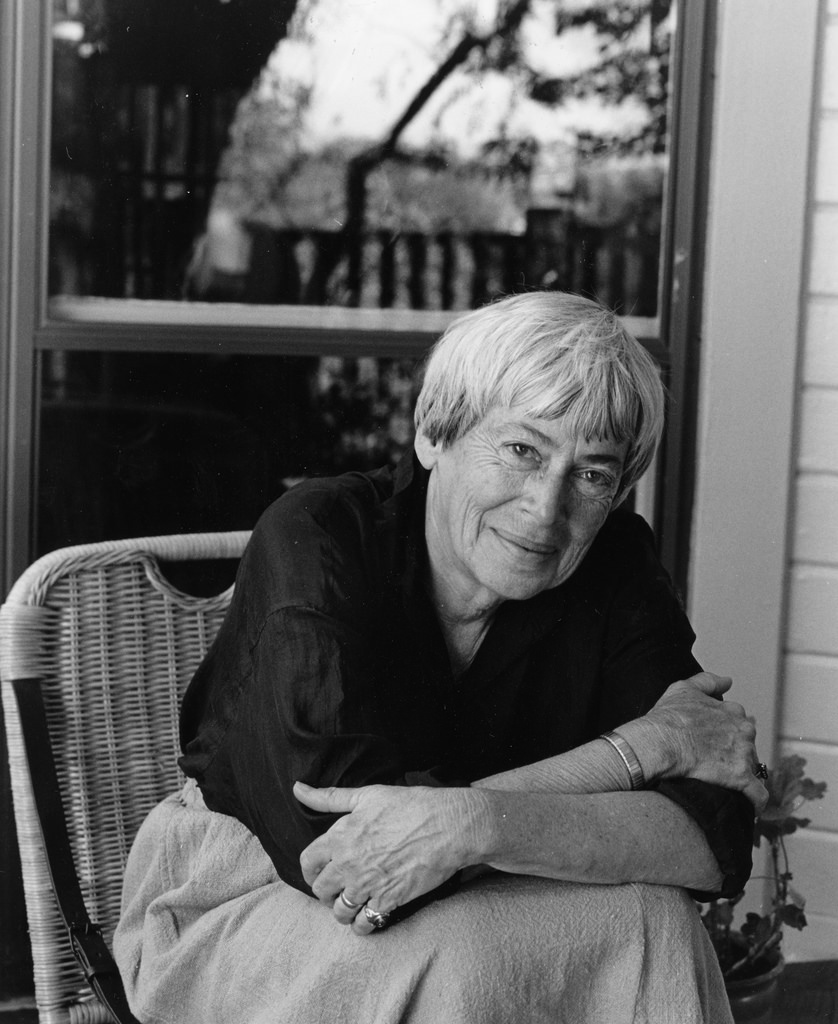

Watching her from the audience, I had the distinct impression that a cat belonged in her lap while she spoke. Le Guin loved cats—especially black cats, who are statistically less likely to find homes because of the superstitions tied to them. She even maintained a blog where she included entries called The Annals of Pard (her cat). She spoke to the feminist magazine I wrote for in college and did a Q&A with our editor for the “Cat Edition.” Her kindness with her time was always admirable.

On stage, she read us an unpublished story about three sisters who folded themselves into male identities to operate their family ranch unprovoked. Then she broke the tension of hundreds of minds settling into sad understanding by sharing a recent discovery that her husband had never read Jane Austen. “’Oh, Charles!’ I said!” Then she laughed and told us that she started reading Emma aloud to him.

Ursula K. Le Guin is a celebrated figure, internationally respected for her revolutionary work in science fiction and fantasy. She pushed boundaries, deconstructed gender, questioned human truths, espoused feminist theory, and did it all with style and humility. She won the prestigious Hugo, Nebula, and Locus awards multiple times for her writing.

She is a celebrated figure at the place where I completed my undergraduate education, as well. The University of Oregon Libraries hold the Ursula K. Le Guin literary papers, which she has been donating to the library’s special collections since the early 1970s. The University of Oregon has a Le Guin Feminist Science Fiction Fellowship to encourage research in feminist speculative and science fiction.

I was thrilled to meet her.

She signed my copy of The Left Hand of Darkness, one of her most famous books, and chatted with me about what I was studying. Her presence wasn’t of the star-striking variety—she carried comfort and familiarity like a coat and wherever she was you thought, ‘Yes, this is normal. This is right, that she is here.’ It feels strange, although I am one near-stranger in a sea of millions, to know that she is no longer in Portland, no longer updating her blog, writing short stories, reading Jane Austen books aloud to her husband. The knowledge of her absence feels unnatural.

Yet, her work is not done. I am reminded of her speech at the 2014 National Book Awards, where she received the lifetime achievement award:

“Hard times are coming, when we’ll be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope. We’ll need writers who can remember freedom — poets, visionaries, realists of a larger reality.”

A parting gift, Le Guin shared a poem she wrote in 1991 as the last entry on her blog.

Writers, we have work to do.

Poem Written in 1991, When the Soviet Union Was Disintegrating

by Ursula K. Le Guin

i

The reason why I’m learning Spanish

by reading Neruda one word at a time

looking most of them up in the dictionary

and the reason why I’m reading

Dickinson one poem at a time

and still not understanding

or liking much, and the reason

why I keep thinking about

what might be a story

and the reason why I’m sitting

here writing this, is that I’m trying

to make this thing.

I am shy to name it.

My father didn’t like words like “soul.”

He shaved with Occam’s razor.

Why make up stuff

when there’s enough already?

But I do fiction. I make up.

There is never enough stuff.

So I guess I can call it what I want to.

Anyhow it isn’t made yet.

I am trying one way and another

all words — So it’s made out of words, is it?

No. I think the best ones

must be made out of brave and kind acts,

and belong to people who look after things

with all their heart,

and include the ocean at twilight.

That’s the highest quality

of this thing I am making:

kindness, courage, twilight, and the ocean.

That kind is pure silk.

Mine’s only rayon. Words won’t wash.

It won’t wear long.

But then I haven’t long to wear it.

At my age I should have made it

long ago, it should be me,

clapping and singing at every tatter,

like Willy said. But the “mortal dress,”

man, that’s me. That’s not clothes.

That is me tattered.

That is me mortal.

This thing I am making is my clothing soul.

I’d like it to be immortal armor,

sure, but I haven’t got the makings.

I just have scraps of rayon.

I know I’ll end up naked

in the ground or on the wind.

So, why learn Spanish?

Because of the beauty of the words of poets,

and if I don’t know Spanish

I can’t read them. Because praise

may be the thing I’m making.

And when I’m unmade

I’d like it to be what’s left,

a wisp of cheap cloth,

a color in the earth,

a whisper on the wind.

Una palabra, un aliento.

ii

So now I’ll turn right round

and unburden an embittered mind

that would rejoice to rejoice

in the second Revolution in Russia

but can’t, because it has got old

and wise and mean and womanly

and says: So. The men

having spent seventy years in the name of something

killing men, women, and children,

torturing, running slave camps,

telling lies and making profits,

have now decided

that that something wasn’t the right one,

so they’ll do something else the same way.

Seventy years for nothing.

And the dream that came before the betrayal,

the justice glimpsed before the murders,

the truth that shone before the lies,

all that is thrown away.

It didn’t matter anyway

because all that matters

is who has the sayso.

Once I sang freedom, freedom,

sweet as a mockingbird.

But I have learned Real Politics.

No freedom for our children

in the world of the sayso.

Only the listening.

The silence all around the sayso.

The never stopping listening.

So I will listen

to women and our children

and powerless men,

my people. And I will honor only

my people, the powerless.

–Ursula K. Le Guin

1991

Sarah Wyer is the Digital & Database Associate for Maryland Humanities. She has an M.A. in Arts Management and an M.A. in Folklore with a focus on gender and art.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed on our blog do not necessarily reflect the views or position of Maryland Humanities or our funders.