For the 23rd season of our Chautauqua living history series, we are commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the United States’ entry into the Great War as three World War I-era figures come to life on the Chautauqua stage. One of those figures is renowned African American activist W.E.B. Du Bois. Dr. DaMaris B. Hill, Assistant Professor of English, Creative Writing and African American and Africana Studies at the University of Kentucky, tells us about Du Bois’s publication for children, The Brownies’ Book.

One hundred years ago, in 1917, the United States of America entered The Great War. My great grandparents were preteens and most likely already working. America was 141 years old and still trying diligently to define what being “American” meant to its citizens and how America would be perceived by the rest of the world. The Original Dixieland ‘Jass’ Band recorded a new genre of music, jazz, that was African and European in origin. It could only be made in America. It was miscegenation music. President Woodrow Wilson declared “The world must be safe for democracy. Its place must be planted upon the tested foundations of political liberty”. And, meanwhile during 1917 and most of the 20th Century the oppressive policies regarding Jim Crow raged. Segregationist policies like Jim Crow and the gender specific Jane Crow (aimed at discriminating against black women) made democracy impossible in a national context. This is most evidenced in the race riots of 1917 such as the East St. Louis Massacre and the Houston Riot.

Born in 1868 of American and Haitian parents, W.E.B. Du Bois was an American intellectual, Pan-Africanist, author, historian, sociologist, civil rights activist and editor. He was a graduate of Fisk University, Harvard University and University of Berlin. He was also instrumental in founding the NAACP and served as a public intellectual over many decades. Along with other American activists such as Ida B. Wells, Mary White Ovington and Henry Moskowitz, Du Bois worked in multiple ways to promote democracy and advocate for democratic policies to be practiced in the everyday lives of African Americans.

It is important that this year’s Chautauqua about The Great War includes discussions about Du Bois’ perspectives regarding national identity, particularly in context of segregation and separatist propaganda. It is also important that we recognize how these perspectives influenced American history and culture. Many publications and much of the literature produced before 1910 sought to define what it means to be “American.” This push to define America can be recognized in context of print capitalism. Print capitalism contributes to the ways “nationhood” is conceived by using technologies, such as the printing press, to stimulate a common language and common discourse in printed books and other media. Print capitalism stimulated a sort of pictorial census of the state’s patrimony even at the high cost to the state’s subjects. This specifically impacted African Americans, Native Americans, and to some extent immigrants and women, because print capitalism promoted segregation and the wide acceptance of second class citizenship in the mainstream media. In many ways, print capitalism was used to make sure that the larger public was convinced that non-white people were second best – at best.

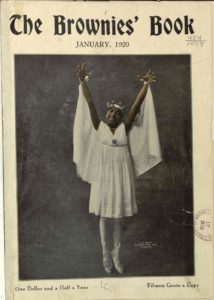

Du Bois used his intellect, networks and influence to create magazines and literature aimed at countering the negative stereotypes African American/Black people were forced to negotiate because of segregationist policies and ideas promoted by print capitalism. One such magazine was The Crisis established in 1910; it was designed to “set forth those facts and arguments which show the danger of race prejudice, particularly as manifested today toward colored people.” Its name was derived from the fact that Du Bois and the other editors believed that the early 20th Century was a critical time in the history of the advancement of men. They also agreed that The Crisis would reflect some sense of nationalism, stating that the magazine “will stand for the rights of men, irrespective of color or race, for the highest ideals of American democracy, and for reasonable but earnest and persistent attempts to gain these rights and realize these ideals.” A decade later Du Bois worked with editors Augustus Granville Dill and Jessie Redmon Fauset to publish another type of magazine, this one for children.

In The Crisis Issue, “The True Brownies” sought to teach Black children about Pan-African Culture, racial identity, and social situations in the Americas and abroad. The editors wanted young readers to know about the history and accomplishments of Black people, domestically and abroad. The contents included poetry, stories, folktales, photographs, art and opinion pieces. In fact, The Brownies’ Book publications promoted and conveyed boundless possibilities to many Black children that because of nationalist propaganda, they did not see in mainstream media. The periodical promoted and inspired self-respect and self-love in Black children and families. In The Best of The Brownies Books Marian Wright Edelman writes, Du Bois’ publications like The Crisis and The Brownies’ Book instilled a sense of life that transcended the artificial boundaries of race, second best citizenship, gender and material things associated with economic wealth. As a result, readers and subscribers were also gifted with a life-long layer of insulation against the ugly voices of doubt, racism and hatred.

Jessie Redmon Fauset used the 24 issues of The Brownies’ Book not only to counter print capitalism, but in some ways to inspire and nurture important artistic vision. It is paramount to note that the Harlem Renaissance emerged and grew at the same moment that The Brownies’ Book was being published and circulated. Fauset published many writers and artists in The Brownies’ Book that would later become iconic figures within the Harlem Renaissance, including writers such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston and Nella Larsen.

Jessie Redmon Fauset used the 24 issues of The Brownies’ Book not only to counter print capitalism, but in some ways to inspire and nurture important artistic vision. It is paramount to note that the Harlem Renaissance emerged and grew at the same moment that The Brownies’ Book was being published and circulated. Fauset published many writers and artists in The Brownies’ Book that would later become iconic figures within the Harlem Renaissance, including writers such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston and Nella Larsen.

When Du Bois published and circulated The Brownies’ Book, he created opportunities and encouraged dialogues between young readers and their parents or guardians, drawing the African American family together and promoting ideas relating to nationalism, democracy, and Pan-Africanism. The Crisis magazine and The Brownies’ Book allowed Du Bois to shape the conversation about nationalism and identity during The Great War. In addition, the publications were bold and necessary statements in and about American culture and by extension fostered several aspects of African American cultural production.

About Dr. DaMaris B. Hill

Dr. DaMaris B. Hill’s work is modeled after the work of in the work of Toni Morrison and an expression of her theories regarding ‘rememory’. She has studied with writers such as Lucille Clifton, Monifa Love-Asante, Marita Golden and others. Her development as a writer has also been enhanced by the institutional support of The MacDowell Colony and others. Her books include The Fluid Boundaries of Suffrage and Jim Crow: Staking Claims in the Heartland and \ Vi-zə-bəl \ \ Teks-chərs \ (Visible Textures), short collection of poems. Hill’s creative process and scholarly research is interdisciplinary and examines the intersections between literature, cultural studies and digital humanities. Hill serves as an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing, English and African American and Africana Studies at the University of Kentucky.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed on our blog do not necessarily reflect the views or position of Maryland Humanities or our funders.