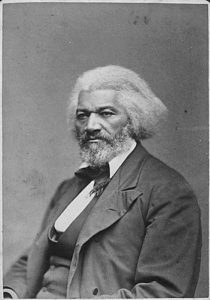

“I am a Marylander and love Maryland and her people. I feel much… affection for this old spot around Fell’s Point where I first felt that I might be useful in advancing and elevating my race, as I do for my birthplace on the Eastern Shore.”

Frederick Douglass,

Baltimore Sun, September 7, 1891

In the years following the death of Frederick Douglass, a groundswell of support arose for an annual celebration to commemorate the life of the famous abolitionist. The establishment of Douglass birthday celebrations marked one of the first widespread campaigns for an annual celebration in honor of an African American leader. In Black communities, “Douglass Day” events emerged along with other regional celebrations including Emancipation parades, Decoration Day and Lincoln’s Birthday.

Although the date of Douglass’s birth remains a mystery (as do the births of many enslaved people), Douglass chose February 14th for his birthday. The year 1817 is the date most commonly cited for his birth.

Douglass Birthday celebrations were typically a mix of pomp and circumstance. Programs opened with rousing renditions of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” or “Just Give us Another Lincoln,” a popular song at the turn of the nineteenth-century. In Baltimore and Boston, the cities’ best speakers took center stage describing scenes from the life of Douglass in slavery and freedom. Many early programs concluded with a stirring poetic elegy by Paul Laurence Dunbar pulling on the heart strings of listeners and especially those who knew Douglass.

Throughout the history of Douglass Birthday celebrations, the reasons to preserve his memory were as varied as the groups who sponsored these events. In the colored schools of New Albany, Indiana, Douglass Birthday celebrations began as early as 1906. For educators, examining the role of Douglass as a freedom fighter served as an important tool in teaching black history in the classroom. In Baltimore, students looked forward to Frederick Douglass essay and trivia contests where contestants competed for authentic bronze Douglass medals.

In Washington, D.C., tourists and local organizations made annual pilgrimages to Cedar Hill in Anacostia on his birthday. This wave of support helped the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC) maintain stewardship of the Douglass home for forty years until it became a historic site of the National Park Service in 1962.

While these celebrations could have vanished in 1926 with the establishment of Negro History Week, independent Douglass events continued to survive well into the mid-twentieth century. Civil rights activists and the Black press used Douglass birthday events to lobby for anti-lynching legislation in the 1930s, the integration of the Armed Forces in the 1940s, and to pray for the Supreme Court while they were deciding school desegregation cases in the 1950’s.

One of the last major events to honor the Douglass birthday occurred in 1967 when the U.S. Post Office issued a Frederick Douglass commemorative stamp for the sesquicentennial of his birth. In Baltimore, a sesquicentennial program was held at Morgan State University featuring a keynote address by the distinguished historian Dr. Benjamin Quarles which was later published in the Congressional Record.

This February 4th, the Reginald F. Lewis Museum and the Baltimore City Historical Society will celebrate Maryland’s native son with a bicentennial birthday lecture from the latest biography Picturing Frederick Douglass with John Stauffer, Ph.D. of Harvard University at the museum at 1pm. For more details please see the museum’s website at lewismuseum.org.

About the Author:

Lisa Crawley serves as the Resource Center Manager at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum in Baltimore. She has worked in the field of public history and educational publishing for the Montgomery County Historical Society, the Drake House Museum and Scholastic Inc. A native of New Jersey, she holds an M.A. in Museum Studies from Hampton University.

The opinions expressed by guest contributors to the Maryland Humanities blog do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Maryland Humanities and/or any of its sponsors, partners, or funders. No official endorsement by any of these institutions should be inferred.