Every day—at book festivals, during classroom visits, in interviews conducted by Skype—writers take part in Q&A sessions with audiences. If you’ve sat in one of these sessions, you probably know the one question a writer is almost guaranteed to hear: “Where do you get your ideas?”

Though common, the question is tough to answer. I usually offer a few sentences, something about keeping my senses alert, studying the world, plumbing my own memories. I confess to bad habits, including eavesdropping. While this response isn’t untrue, it feels inadequate. The reality is, the origins of a story—or a poem, a song, a painting—can be hard to articulate. A character gesture, fleeting image, or line of dialogue might have launched a project, but—like one of Andy Goldsworthy’s outdoor sculptures, leaves stitched together with pine needles, say—it’s altered by weather and time.

What if, instead, we considered the question, How do you take care of your ideas? Once one of these seeds starts to seem viable, what next?

Ideas come when you’re open to them. And it’s with that same spirit of openness that you develop the ideas. You move forward, being willing to upend, redirect, or tinker. You listen to what the stories—or essays, or poems—are telling you they want to be about. You note interesting connections your subconscious is making, ones your conscious mind wasn’t aware of. When you finish a draft, you look at what’s working and what isn’t, tease out themes or character traits, delete some passages, expand others. Then you ask for feedback from readers and revise some more.

In short, you put in the hours. Just as the more regularly you exercise, the easier it is to lace up your running shoes, the more you write, the more ingrained the habit. Writing begets more writing.

In general, the most steadily productive writers I know don’t treat their writing as overly precious. They just do it. They find a rhythm that works for them. It might be every day—or not. Sometimes they feel like a genius, and other times, a miserable fraud. But they keep going.

Some writing sessions won’t yield much, but others will take you so deep into your project, you’ll exist in a sort of creative dream state. Circular as the logic may seem, through the act of writing itself, you’ll figure out what you mean to say.

To be fair, even when you do invest the time, not every idea will prove viable. Sometimes a project just needs to be put aside, to give it—or you—time to mature. Other ideas may never work out. That’s just part of the process.

I say all this as much to remind myself as to tell you. There are ideas I’m not tending very diligently, even as I speak. But talk to me next week, when one of my projects is humming again, and I’ll tell a different story.

Elisabeth Dahl writes for both children and adults. Her first book, Genie Wishes, was released in 2013. Her short stories, essays, and poems have appeared at NPR.org, The Rumpus, the Johns Hopkins Magazine, and other outlets. Born in Baltimore, she went on to study literature and writing at Brown, Johns Hopkins, and Georgetown universities. After working as a freelance copyeditor and proofreader in Washington, DC and the San Francisco Bay Area, she moved back to Baltimore, where she teaches writing through Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Talented Youth.

“Finding and Cultivating Your Ideas” was first produced as a piece on Humanities Connection. Listen to Elisabeth Dahl read the essay on Humanities Connection.

Duke Ellington is considered one of America’s greatest composers. Born in 1899 in Washington, DC, Ellington was an incomparable showman who was one of the greatest composers of the twentieth century with a career that spanned over fifty years. With over 300 compositions over his lifetime, Ellington was posthumously awarded a special Pulitzer Prize “commemorating the centennial year of his birth, in recognition of his musical genius, which evoked aesthetically the principles of democracy through the medium of jazz and thus made an indelible contribution to art and culture.”

Duke Ellington is considered one of America’s greatest composers. Born in 1899 in Washington, DC, Ellington was an incomparable showman who was one of the greatest composers of the twentieth century with a career that spanned over fifty years. With over 300 compositions over his lifetime, Ellington was posthumously awarded a special Pulitzer Prize “commemorating the centennial year of his birth, in recognition of his musical genius, which evoked aesthetically the principles of democracy through the medium of jazz and thus made an indelible contribution to art and culture.” Gwendolyn Brooks was an African-American poet whose works illuminated the

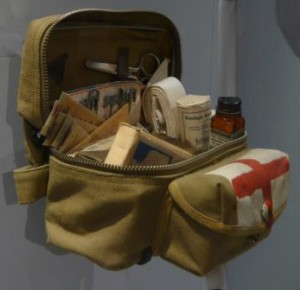

Gwendolyn Brooks was an African-American poet whose works illuminated the Ernest Hemingway was one of the greatest American literary figures of the twentieth century who continues to influence modern literature with his trademark style of simple yet perceptive prose. Born in 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, Hemingway’s experiences abroad as a foreign correspondent and as an ambulance driver for the Red Cross during World War I greatly influenced his literary works, such as A Farewell to Arms. Hemingway’s hobbies, including big game fighting, bull-fighting, and deep-sea fishing, also influenced his writings, particularly his novel The Old Man and the Sea which earned him the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1953 and led to the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954.

Ernest Hemingway was one of the greatest American literary figures of the twentieth century who continues to influence modern literature with his trademark style of simple yet perceptive prose. Born in 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, Hemingway’s experiences abroad as a foreign correspondent and as an ambulance driver for the Red Cross during World War I greatly influenced his literary works, such as A Farewell to Arms. Hemingway’s hobbies, including big game fighting, bull-fighting, and deep-sea fishing, also influenced his writings, particularly his novel The Old Man and the Sea which earned him the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1953 and led to the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954.

Over the years I have developed a partnership with The National Park Service (NPS), “America’s Best Idea.” In conjunction with the approaching 100-year anniversary of the NPS, my students have been working with The President’s Park in Washington D.C. on a project called “The White House Centennial Project.” Over this past year my students have not just been learners of the history of the United States and its Presidents at the White House, but now have transitioned into teachers of this vital history themselves. They have created investigations for future students to conduct both in the White House Visitor Center and outside on the grounds of the park itself. Investigations range from questions like “How does the White House change during the time of war?” to exploring the effects of climate change on the treasured memorials in the park. They ask students to assess damage of both physical and chemical weathering on the memorials and statues and problem solve solutions to fixing the damage. Perhaps the most exciting investigation is interviewing protestors north of the White House. What are they protesting? What are their goals? How would you come up with a compromise to please both parties? To learn more about this project check out their work on our blog:

Over the years I have developed a partnership with The National Park Service (NPS), “America’s Best Idea.” In conjunction with the approaching 100-year anniversary of the NPS, my students have been working with The President’s Park in Washington D.C. on a project called “The White House Centennial Project.” Over this past year my students have not just been learners of the history of the United States and its Presidents at the White House, but now have transitioned into teachers of this vital history themselves. They have created investigations for future students to conduct both in the White House Visitor Center and outside on the grounds of the park itself. Investigations range from questions like “How does the White House change during the time of war?” to exploring the effects of climate change on the treasured memorials in the park. They ask students to assess damage of both physical and chemical weathering on the memorials and statues and problem solve solutions to fixing the damage. Perhaps the most exciting investigation is interviewing protestors north of the White House. What are they protesting? What are their goals? How would you come up with a compromise to please both parties? To learn more about this project check out their work on our blog: