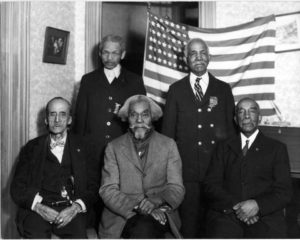

In 1915 on the fiftieth anniversary of a parade of Union soldiers that marched down Pennsylvania Avenue at the end of the war, a group of Black Civil War veterans of the Grand Army of the Republic, a Civil War veterans’ organization, formed a “Committee of Colored Citizens.” Their cause was the collection of funds to accommodate Black veterans visiting Washington, DC for the anniversary. The Committee later took on a new cause – advocating for a “Negro Memorial” and a national museum.

One year later, U.S. Representative Leonidas C. Dyer, a Republican from Missouri, introduced HR 18721, a bill that called for a commission to “secure plans and designs for a monument or memorial to the memory of the negro soldiers and sailors who fought in the wars of our country.” Throughout the twentieth century, there were numerous attempts to establish a memorial to Black Americans in Washington, DC. It wasn’t until 2001, when President George W. Bush signed Public Law 107-106, forming a Presidential Commission to develop an implementation plan for the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), that the process got underway.

The NMAAHC opened the weekend of September 24 and I managed to score two timed-entry passes to one of the hottest events in DC (If you don’t believe me, take a look at how many timed-entry passes are for sale on Stub Hub). I was accompanied by my mother as we huddled on the lawn next to the beautiful museum building designed by David Adjaye. We desperately clutched our passes for 12:15pm as we moved with the huddled masses into the building. Once inside, we decided to start at the top of the museum and work our way down. The museum is meant to be viewed from the bottom-up, starting with the founding of our country and the enslaved labor it was built upon. As you move up through the museum, the narrative of the Black experience in America is fleshed out: Civil War, Reconstruction, the long Civil Rights Movement, and the election of the first Black president. But the museum does so much more than that. It is a celebration of all the contributions that Black people have made to America, whether it was in sports, medicine, food, music, or television.

While the museum and its vast collection is impressive by itself, the most lasting impression that I felt that day was left by the other visitors. Having visited and worked in museums, it was a unique experience to watch so many people be visibly moved by the museum. People reminiscing about the good ol’ days as they looked at television clips from Good Times or danced to the music of Stevie Wonder. The hushed tones that hung over the room as people walked by the casket of Emmett Till or stared into the eyes of a Ku Klux Klan hood. This place is a pilgrimage site that I hope everyone gets an opportunity to visit.

Timed-entry passes are sold out through March 2017. While you wait, you should take advantage of the many local Black museums that have been serving their communities for decades. We have the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument in Dorchester and Caroline Counties; National Great Blacks in Wax Museum, the Frederick Douglass-Isaac Myers Maritime Park, and the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African-American History and Culture in Baltimore; the Banneker-Douglass Museum in Annapolis; the Prince George’s African American Museum and Cultural Center in North Brentwood; the Diggs-Johnson Museum in Woodstock; and the Charles H. Chipman Center in Salisbury. These local institutions should be celebrated, as they are the foundations upon which the NMAAHC was built.