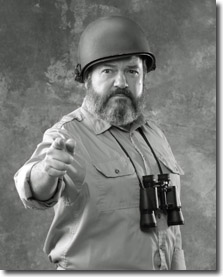

Our Chautauqua event is underway and in preparation for the free performances, we spoke with the scholar-performers headlining the events. The performances run from July 5th to July 16th. This week’s interview is with Brian Gordon Sinclair, performing scholar of Ernest Hemingway.

Q. What drew you to Hemingway as a character?

Sinclair: Hemingway’s public persona as a hard-drinking womanizer, although partially true, was mostly a creation of the media. If you read both his stories and the biographies, especially Michael Reynolds’ superb five volume series, you will discover much compassion in Hemingway. He risked his life to save his youngest son from sharks; he donated money to the veterans of the Lincoln Brigade; he worked to free Ezra Pound from a mental hospital; and he used his modest but effective medical knowledge to save the life of his last wife, Mary, when she almost died from a tubal pregnancy. A simple but particularly touching example occurred when Ernest wrote a letter of consolation to his friends, Gerald and Sara Murphy when their son Baoth died. Hemingway spoke of how words were so inadequate at such times and concluded with a statement of kindness and awareness which I have paraphrased:

Sinclair: Hemingway’s public persona as a hard-drinking womanizer, although partially true, was mostly a creation of the media. If you read both his stories and the biographies, especially Michael Reynolds’ superb five volume series, you will discover much compassion in Hemingway. He risked his life to save his youngest son from sharks; he donated money to the veterans of the Lincoln Brigade; he worked to free Ezra Pound from a mental hospital; and he used his modest but effective medical knowledge to save the life of his last wife, Mary, when she almost died from a tubal pregnancy. A simple but particularly touching example occurred when Ernest wrote a letter of consolation to his friends, Gerald and Sara Murphy when their son Baoth died. Hemingway spoke of how words were so inadequate at such times and concluded with a statement of kindness and awareness which I have paraphrased:

“All we can do is to live it now, a day at a time…and be very careful not to hurt each other.”

I read that line at a time in my life when I was struggling and striving towards an understanding of the compassionate nature. Hemingway helped me to understand.

Q. What is your favorite work by Hemingway?

Sinclair: An impossible choice; however, after spinning the mental dial, I have selected For Whom the Bell Tolls. This story of the Spanish Civil War is one of the great dramas of the twentieth century. It was a favorite of Fidel Castro who said that it taught him all the tactics he needed to know to fight a guerilla war. A supporter of the Republican government, Hemingway knew that his story of a fight for freedom combined with a passionate romance that literally made the earth shake would lay bare the atrocities of both sides of the conflict. For Whom the Bell Tolls is high drama indeed…and a great read.

Q. Hemingway’s writing style has been described as simple yet perceptive, which differed from his contemporaries. What do you think influenced his style of writing?

Sinclair: There is no doubt that Hemingway’s time in Paris during the years of “the Lost Generation” – Gertrude Stein’s “salon” gatherings which included the likes of James Joyce, Pablo Picasso, and Ezra Pound – was the definitive period when his writing skills were honed and polished. However, there were two other factors always exerting their strong influence: Hemingway’s youth in Illinois and Michigan under the guidance of a father who made young Ernest a keen observer of nature and his first newspaper job with the Kansas City Star. Their style guide included such instructions as: “Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English. Be Positive. Never use old slang and eliminate every superfluous word.” Those were the best rules he ever learned for the business of writing, and he never forgot them.

Q. If you could go back in time to meet Hemingway, what would you say to him?

Sinclair: If I could meet with Ernest, I would share with him some of the modern understandings of alcohol, of depression, of concussions, and of the side effects of various medications. I might even suggest avoiding a barbaric technique called electro-convulsive therapy (ECT). After this serious discussion, I would simply ask to sit quietly with him on the deck of his boat, Pilar, calmed by a gentle breeze floating over a peaceful view of a beautiful Gulf Stream. I would thank him for being the mirror through which I could view my own life. We would share cool drinks, sigh a few sighs and finally I would look at him and say, with the utmost affection, “Well done, old friend, well done!”

Q. Hemingway once stated that “Writing at it’s best is a lonely life.” How do you as a performer strike the balance that is Hemingway’s machismo in his perceived public persona and his internal struggles with mental illness?

Sinclair: To present a balanced Hemingway was surprisingly simple.

All I had to do was to tell the story of Ernest Hemingway but I had to tell the whole story and I had to tell both sides of that story and it was a huge story. Hemingway knew that you had to live with your demons and your angels. You had to alternate the braggadocio with the compassion. It makes Ernest more human and more enjoyable, to play and to watch. Eventually, when Ernest went through ECT and succumbed to dementia, the world broke him. For these moments, I had to tap into the deepest, most painful memories in my own psyche. Eventually, the character of Ernest Hemingway and I were able to blend into a successful theatrical presence. Hemingway had become my hero and I was bound to respect him in performance. As Ernest himself said, “As you get older, it is harder to have heroes but it is sort of necessary.”

Q. What is the main thing that you have gained from your work on Hemingway?

Sinclair: Hemingway opened a doorway that allowed me to discover the vibrant love of literature and people of Cuba. His spirit is still there and nowhere is it stronger than at his home, Finca La Vigia (Lookout Farm). Now that Hemingway has moved into legend, I have the pleasure of sharing that legend. The modern reincarnation of the children’s baseball team that Ernest started in the 1940s has honored me by choosing me as its Patron. Treated as Hemingway II, on the first Saturday of every December, I recreate an authentic holiday celebration at the Hemingway estate for the members of the team. It is my great pleasure to invite everyone to what is, for this special day, my home. Come and meet the warm, friendly, generous people of Cuba.